I BET some readers still remember using an outside lavatory where they lived.

Perhaps it was in an adjoining outhouse with a flush system, while some might even remember the privy some distance from the house down the garden path.

Typically these privies were in more rural locations and were not connected to a water supply. It usually took the form of a tiny wooden or tin shack. More luxurious examples were brick-built and may have even had a small window on the side.

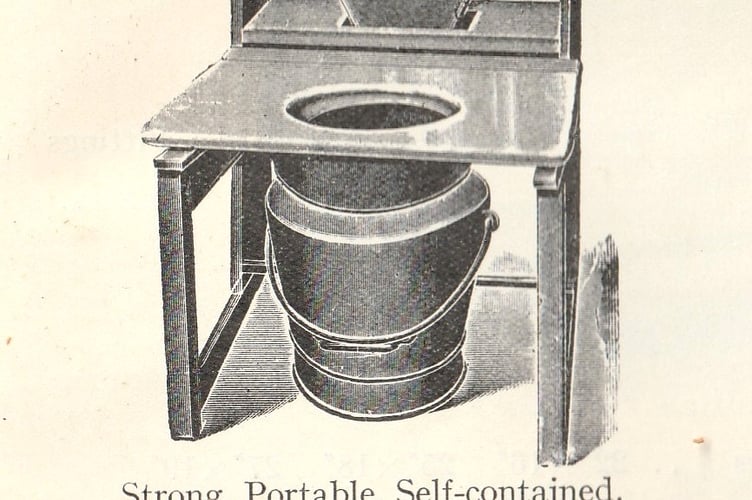

Inside was a flat wooden board with the appropriate hole from which the user’s bottom hovered over, with a bucket underneath. You get the idea of what happened next!

Local historian John Janaway (a good friend of mine, who sadly died a few years ago) wrote a book, Surrey Privies (published in 1999), after going on a search of old privies and found quite a number still standing.

John also interviewed people, asking them to describe their memories of them. He wrote: “A night visit was only for the desperate when, clutching a guttering candle or oil lamp, they made their faltering way towards the blackness, the spider and the bogeymen.”

Within his research John learnt that some cottages in Pirbright had movable privies. A hole was dug in the garden and the privy, a simple wooden shed, was balanced over the hole. When the hole was full, a new hole was dug in the garden.

One person told him: “We used to have a bucket of ashes from the fire on the floor in the dunny as we called it and, after you had been, you had to sprinkle some ashes down the hole to cover what you had done. The dry ashes seemed to kill off a lot of the pong.”

Ashes or fresh soil was also sprinkled on the fixed privy with its bucket. When full, the contents was used to fertilise the vegetable patch, unless the cottage was on the list of the night soil men, who made a weekly call to take away the waste.

Also known as “lavender men”, the bucket would be brought up the garden from the privy for the men who then emptied the contents into their “lavender van”. They then cleaned and disinfected the bucket for you.

Privies rarely had a lock or bolt on the door, and some people resorted to singing loudly to let others know it was occupied. Sometimes a piece of string was attached to the inside of the door and the door left open to let air in. If someone was heard approaching, the string was pulled to shut the door without the occupant having to get off the seat.

One privy in Surrey that was some distance from the house had a flagpole outside the door. A Union Jack would be raised to warn others the privy was occupied and therefore a long trek down the garden would be in vain.

A far back as 1860, the Rev Henry Moule of St John’s College Cambridge and vicar of Fordington in Dorset patented a mechanical earth closet which used dried earth or ash to cover the contents of the bucket.

The earth or ash was tipped into a hopper behind the sitter and upon pulling or lifting a lever, a quantity of earth or ash was deposited on top of the latest waste.

It can be said Moule’s invention was very successful and were being made and sold into the 1930s, at least.

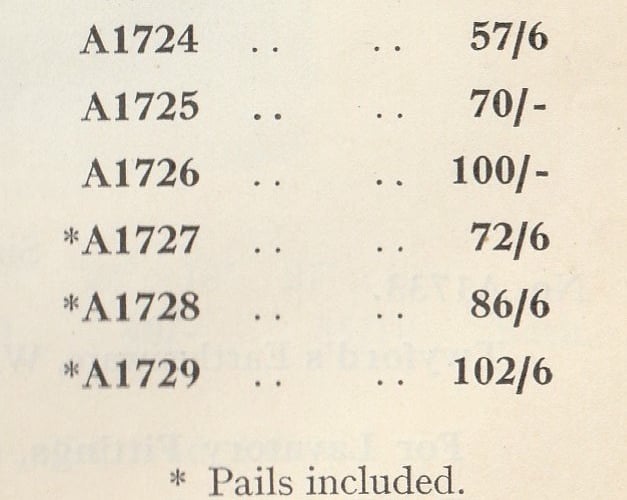

My copy of the 1936 edition of Woking wholesale ironmongers and builders’ merchants Skeet & Jeffes’ catalogue indeed features Moule’s patent earth closets.

Several models were available, starting price being 57 shilling and six pence (about £145 today) to 102 shillings and sixpence (£259).

In his book, John Janaway noted that earth closets were still being used in some rural parts of Surrey even into the early 1990s.

.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.