By September 1938 many believed war with Germany would be inevitable at some stage.

That must have been perceived to be even more likely for readers of the News & Mail, when in its edition of 16 September 1938 it published plans being put into place by Woking Urban District Council and the Air Raid Precaution (ARP) service as the threat of war had recently escalated.

Here are some of the details that were featured.

The chairman of the council, Conrad Samuel, urged people not to become “panicky,” as the council had, for months past, been accumulating vast amounts of equipment “to meet such an emergency as now threatened,” and for three years had been “building up an air raid precautions organisation”.

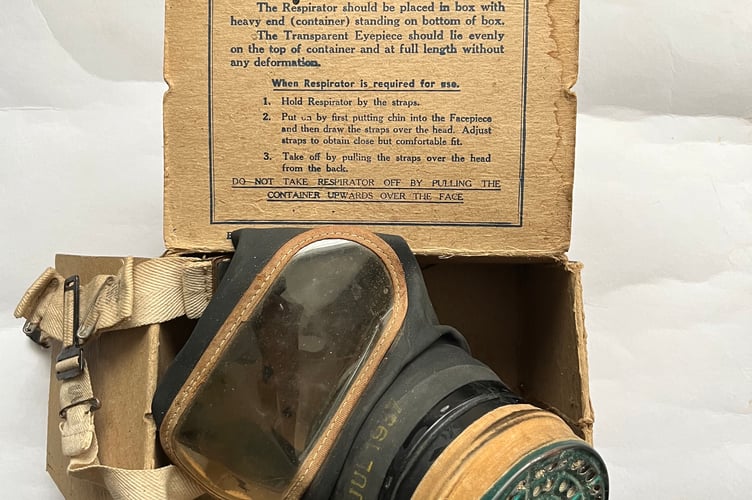

He added: “We have had our gas masks, 36,750 of them, stored for some time,” and “deliveries are already taking place”. These would be delivered to people’s homes by ARP wardens.

The ARP had provided for four first-aid posts at Knaphill, Westfield, Horsell and West Byfleet, with 15 mobile first-aid parties (of four persons each) soon to be mobilised.

Other volunteers already enrolled included 220 first-aid workers; 625 air-raid wardens; 30 electrical assistants; 40 despatch riders; 150 rescue and demolition, decontamination and repair workers; 20 lorry drivers; plus 70 girls assembling gas masks.

Advice on the care of gas masks included: “Persons are advised to keep the respirator away from damp and from artificial heat, and children should not be allowed to play with it.”

The report noted that questions had been asked of the local authority as to what would happen in the event of the canal bridges being blown up. Mr Samuel replied that arrangements had been made “by which bridges will be thrown across the canal to connect Horsell with Woking within a very short period of the destruction of the existing bridges”.

Although many people had joined the ARP service, Mr Samuel appealed for more volunteers, adding: “To be prepared and to know that if the time of need should come that help is ever present, is Woking’s aim, and I hope all will work towards that end.”

Trenches were being dug for people to shelter in, if needed, and it was reported that “Many private residences have followed the official advice by providing a trench shelter in their own gardens. The local authority is also busily engaged on making a system of trench works in various parts of the urban district to provide public shelter for any who may need it.”

However, waterlogged ground was proving a problem when digging these trenches, especially in “thickly populated districts like Walton Road, [where] one cannot dig a trench to any depth without finding water”. The report then added: “The trenches are not being covered at the moment.”

There was also advice given to reduce animal suffering in the event of air raids. These included: “Gas-proofing dog kennels, except in places where a large number of dogs are housed, is not recommended. The best advice is to take them into the owner’s gas-proofed room,” and “care should be taken to keep cats indoors at night to avoid the difficulty of finding them should a warning be given”.

People had been stockpiling food, the News & Mail reported, and stated that the Board of Trade had said there was “no need for panic”.

History reminds us of the famous “peace in our time” moment a couple of weeks later on 30 September 1938, when Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned after talks with Adolf Hitler. Standing in the rain at Heston Aerodrome, where his aircraft had landed, Chamberlain held aloft a piece of paper with the nonaggression pact that reaffirmed “the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.”

Of course, this lasted only until 3 September 1939 when Britain declared war on Germany after the Nazis had invaded Poland.