This week we continue the story of the murder at the Blue Anchor Hotel in Byfleet 100 years ago, when landlord Alfred George Poynter Jones was poisoned with strychnine by Jean-Pierre Vaquier, who was having an affair with the landlord’s wife.

After Vaquier’s arrest, his picture was published in newspapers in an appeal for information regarding the poison he had been accused of having used.

Horace Bland of W. Jones & Co, Southampton Row, London recalled Vaquier had visited his chemist’s shop to buy various chemicals that he said were for wireless experiments.

However, on 1 March he sold 20 grains of perchloride of mercury and 12 grains of strychnine to Vaquier.

Mr Jones was buried in St Mary’s Churchyard, Byfleet on 4 April, 1924. However, on April 25 his body was exhumed by the authority of the Home Office.

The News & Mail reported the exhumation party arrived at 11.30pm. It was raining and the work was performed by the light of lanterns, thus creating an eerie effect. The coffin was raised shortly after midnight and taken to a mortuary in West Byfleet.

Sir Bernard Spilsbury, the renowned Home Office forensic pathologist and expert on poisons, conducted a second post-mortem examination.

He found that the corpse’s stomach contained one-fifth of a grain of strychnine, one-third of a grain in the liver, and in the small intestines one-thirteenth of a grain. A fatal dose being half-a-grain.

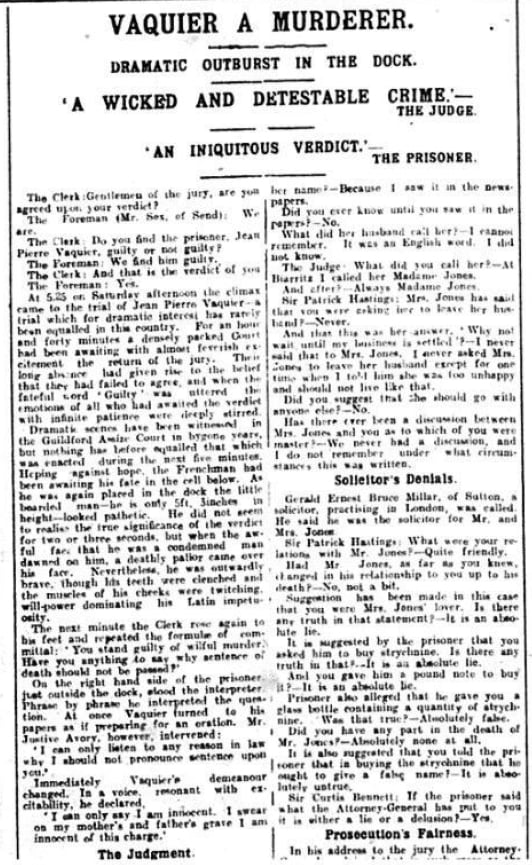

The News & Mail extensively reported the murder as more items of evidence came to light. Initially there was an inquest at Byfleet Village Hall, various hearings at Woking Magistrates’ Court and then the trial.

Vaquier’s trial took place at Guildford Assizes from July 2 to 5, 1924.

Sir Bernard Spilsbury’s evidence was a detailed account of the conditions of the body, the effects of strychnine and the constituents of Bromo-Seltzer, an efferent powder remedy, taken with water.

Taking the witness stand, Vaquier adopted a vain and confident disposition. He denied all responsibility for the murder and tried to blame staff at the Blue Anchor. In spite of having just a few shillings to his name, he spoke of lending Mr Jones £150 and buying 25 grammes of strychnine to destroy a dog.

He called no witnesses in his defence and the jury returned a guilty verdict. Vaquier was sentenced to death and was dragged from the court shouting abuse.

On July 9 Vaquier divulged the location of the hiding place of his poison – within a hole in a wall, covered with some loose bricks, behind a shed of the Blue Anchor’s garden – presumably in the hope of clemency for his death sentence.

Police officers went there and found two glass bottles with metal screw caps, one containing a corrosive strychnine poison in liquid form, and the other containing no less than 23 grains of strychnine crystals. Apparently enough strychnine to kill 700 adults.

If the police had located this large stash of strychnine prior to Vaquier’s trial, and it had not been able to prove all of it belonged to Vaquier, it may have resulted in a different outcome. However, the police never discovered exactly where and by whom this large quantity of poison was obtained.

The day of Vaquier’s execution was set for 12 August 1924 at 9am. Outside the prison gates hundreds of people gathered.

Vaquier went to bed at 8pm the previous day still under the illusion that the hanging would not be carried out.

On the morning of his execution Vaquier wore his black coat and waistcoat that he had worn at his trial. He had a small breakfast of bread, butter, several coffees and a French cigarette.

There was a priest present and just before his execution Vaquier exclaimed “Vive la France!” And in just over a minute that was it – the murder at the Blue Anchor had been avenged, in what was described at the time as one of the grimmest known at any recent London hanging.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.