Woking’s Invalid Convict Prison was still under construction in 1858 when the man recorded as Prisoner No.1 was sent there – and was tasked to help to build it!

The prison, built on heathland at Knaphill, consisted of two wings, one for the sick and insane and the other for more able-bodied convicts. It later became Inkerman Barracks.

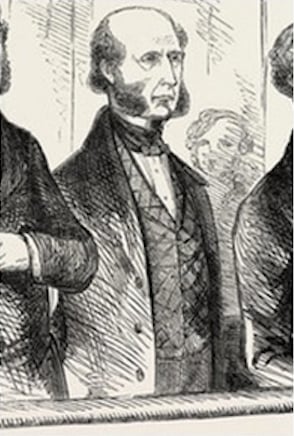

Prisoner No.1 was William Strahan, a banker, who was convicted with two business partners of fraud. He was born on 2 August 1807 to Robert and Margaret Snow, but later changed his surname to Strahan.

His father was a wealthy partner in one of the oldest banks in Britain, which could trace its lineage to the early part of Charles II’s reign.

After studying at Eton and Cambridge, Strahan himself pursued a career in banking at his father’s firm of Snow, Snow, Strahan, Paul & Paul. He later became a partner in the business, it eventually becoming Strahan, Paul & Bates.

It was on 1 January 1851, Strahan, alongside business partner J.D. Paul and, to a lesser extent, his other partner Bates, began to commit a most scandalous Victorian crime.

The Reverend Dr John Griffith, Doctor of Divinity and Canon of Rochester Cathedral, banked with Strahan, Paul & Bates and regularly asked it to make small investments on his behalf.

The relationship was a beneficial one, with both parties benefiting from the profits, until Reverend Griffith asked the bank to invest in Danish five per cent bonds. Between 4 February 1850 and 16 April 1851, he directed the bank to invest a total of £5,000 in bonds. This worked for a time, the bank received its fee and the Reverend Griffith received his dividends.

Reverend Griffith then heard rumours that Strahan, Paul & Bates had gone bankrupt, which soon proved correct. Enquiring about the state of his bonds, he was told by Bates and Strahan that they were either sold or pledged. He then engaged his solicitors to begin formal legal proceedings.

The three bankers were arrested and put on trial. An examination of the bankruptcy of the firm at the time found that as little as six years before the business was solvent: there was a deficiency of £110,000 but Strahan had £100,000 in unencumbered assets and Paul had £30,000.

The defendants pleaded not guilty but at the end of the trial, that took place in October 1855, they were found guilty and sentenced to 14 years transportation.

However, Strahan was not sent overseas and was first imprisoned at Newgate and then on to Millbank Prison, then to Lewes Prison and finally to Woking Invalid Convict Prison in April 1858.

Strahan was released on 21 October 1859 and moved with his wife and six of their children to Blackmore Hall, Sidmouth, Devon. He died on 2 July 1886 in Perugia, Italy.

Thanks go to enthusiastic young historians Daniel Shepherd and Gem Minter who have researched the story of William Strahan as part of their studies into Woking Invalid Convict Prison and the inmates once housed there. They have formed the Institutional History Society, dedicated to exploring England’s institutional system in the 19th century.

Its website can be found at www.institutionalhistory.com

If you have some memories or old pictures relating to the Woking area, call me, David Rose, on 01483 838960, or drop a line to the News & Mail.

For the full story, get the 24 October edition of the News & Mail